My "Field Of Dreams" Is In Coney Island

Watching the Brooklyn Cyclones play never gets old, and while I'm in their magical ballpark, neither do I!

While growing up, I often heard how much more fun Brooklyn was before I was born, which I tried hard not to take personally. One prime example was how the Dodgers had shamelessly abandoned Brooklyn for the sunnier and greener (in terms of cash) environs of Los Angeles. Another was the decline of Coney Island’s world-renowned beachfront amusement parks, culminating with the closing of Steeplechase Park and Brooklyn’s Eiffel Tower, the majestic Parachute Jump.

So, you can imagine my excitement when I heard that the New York Mets would be moving one of their minor league teams to a new ballpark on the historic Steeplechase Park site. In one fell swoop, baseball would at last return to Brooklyn while Coney Island would be restored to some semblance of its former glory. I was floating on air in June 2001 as I passed through the turnstiles of Keyspan Park (named for a local sponsoring utility), which immediately became my personal field of dreams and fountain of youth. In the 23 years since, I’ve been back to Keyspan/MCU/Maimonides Park to watch the Brooklyn Cyclones play 268 games (taking 155 of them, for an impressive .579 winning percentage).

Seeing the Cyclones never gets old—and while I’m in their magical ballpark, neither do I! Whatever issues I face in life or work, whatever real-life troubles are front of mind, whatever aches and pains wear me down, all negative thoughts and feelings are washed away as I walk along the park’s promenade to observe the starting pitcher warm up in the bullpen, eagerly awaiting the first pitch. I was so deeply committed to the team that I often listened to Cyclones games on Kingsboro Community College radio, with both play by play and color commentary provided for 11 seasons by the folksy and colorful Warner Fusselle, long known for being the voice of TV’s “This Week In Baseball.”

The ballpark only has room for about 8,500 fans, so in their first season and even for a few years afterwards a Cyclones ticket was one of the hottest in town and sellouts were common. Tickets were scalped outside the gates, and I had to get on line three hours early to get a good seat for the 2001 playoffs. I bought season tickets for a few years, attending an amazing 31 games in both 2004 and 2005, and 25 games each of the next two seasons.

That inaugural year was enchanting, even though it ended in tragedy. The Cyclones had an explosive offense, led by slugging leftfielder Frankie Coor (.302 with 13 homers and 46 RBIs in 61 games) and speedy centerfielder Angel Pagan (.315 with 30 stolen bases in 62 games), winning 11 of the 13 games I attended. They made it to the championship series and were tied 1-1 with a deciding third game against Williamsport looming in Brooklyn on Sept. 11, 2001. But that game was cancelled for obvious reasons and never rescheduled, leaving the Cyclones as the first co-champions in any sport.

Each year, the Cyclones roster turns over, as a new set of recruits come aboard via the amateur draft among American high school and college players, along with international free agents signed from Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and other baseball crazy countries. In fact, if players are on the team more than one season it usually means their situation is precarious, as successful kids are expected to quickly move up the ladder or out of the system. That means you never know what kind of team you’re going to get from one year to the next. I learned that the hard way, as the Cyclones lost 13 of the 19 games I attended in their second season. Yet even though they finished way out of the playoff hunt, I loved going to the ballpark just the same.

While seeing the Cyclones win is certainly more fun than when they lose, whether in a particular game or over an entire season, a negative outcome doesn’t linger as it does when the home team fails in the Major Leagues—especially given the huge expense of tickets and concessions compared with Brooklyn, where you can get the best seat in the house for $22. It’s an entirely different, more laid-back atmosphere. In that first season a story in the local paper quoted diehard Cyclones fans criticizing those who booed when a player struck out or made an error, pointing out these are just kids in their first professional games, many from foreign lands, desperate to do well so Brooklyn isn’t the end of the road. To this day I don’t recall any booing no matter how poorly the Cyclones play.

The existential challenge facing these kids was brought home to me when I stopped by the visiting bullpen before a Cyclones game during the early years to chat with a beefy lefthanded pitcher who was the nephew of a work colleague. When I asked how it was going, he confessed to having a much harder time than expected. “Wherever I’ve played—from Little League to high school to American Legion ball—I was not only the best player on my team, but in my entire league. Here, in one of the lowest levels of the minor leagues, everyone was the best where they came from, and my best pitches are getting hammered.” The kid hung on for two seasons before returning home to attend college, getting his degree in physical education and ending up coaching college ball.

Part of the charm of minor league baseball for me is watching young players develop, with the best rising to higher and higher levels, although only a special few reach the Major Leagues. I love to scout each season’s squad, looking for diamonds in the rough, assessing individual strengths and weaknesses, and predicting which ones have the best chance of making the Mets. I keep track of my favorite players as if they were my own kids, following them even if they’re released, traded to other organizations, or leave the Mets by choice as free agents to seek bigger bucks or better opportunities elsewhere.

On the first floor of Maimonides Park, there is a Wall of Honor showing all the Cyclones who played in Major League Baseball. As of this blog, 99 former Cyclones have made it to “The Show,” including a bunch of current Mets—Pete Alonso, Brandon Nimmo, Francisco Alvarez, Brett Baty, Tylor Megill, David Peterson, Tomas Nido, Jose Butto, and, most recently, Christian Scott. Other former Brooklyn stars who ended up under the bright lights of Shea Stadium or Citi Field include Scott Kazmir, Michael Conforto, Amed Rosario, Daniel Murphy, Seth Lugo, and Lucas Duda. (See the postscript to this blog for my list of the “Greatest Cyclones Of All Time” at each position.)

But some of my favorites were those who excelled with the Cyclones but for whatever reason (often the inability to hit a curve ball or perfect more than one effective pitch) never made it to the majors. Among those strivers who came up short yet stood out for me are Phillip Evans (a real-life Crash Davis-type who has only played 121 Major League games over four seasons but has racked up 3,973 at bats in 1,111 minor league games, and counting) and L.J. Mazzilli (son of my former high school classmate and Mets World Champion, Lee Mazzilli).

But the best of this unfortunate lot was Ambiorix (who I called “Sonny”) Concepcion, a five-tool player who could hit for average and power, flew around the bases, and had a great glove and rifle arm in rightfield. In 2004 with Brooklyn, he hit .305 with 8 homers and 46 RBIs with 28 stolen bases, but never made it past AA, two steps below the majors. I lost track of Sonny after 2010 as he bounced around the Mexican League, the Dominican Republic, and the independent United League before calling it a day.

A parade of former Met favorites also cycled through to manage the Cyclones, including Tim Teufel, Mookie Wilson, Howard Johnson, and Wally Backman, adding some Major League shine to the games.

Baseball is only half the fun with the Cyclones

The Cyclones go all out to keep fans entertained between innings, starting in 2001 with Party Marty and continuing today with King Henry, running all sorts of crazy contests for kids and adults. The mascots are a hoot, featuring Sandy the Seagull (roly-poly at the start, but became quite lean and buff over the years), who roams the park to everyone’s delight with Pee Wee and his propeller beanie. The nightly highlight is Nathan’s Hot Dog race, with my favorite, the beleaguered Relish, losing every time that first season to Mustard and Ketchup in more and more outrageous ways. (One time Relish was way ahead but stopped to sit in Santa’s lap on “Christmas in August Night.” During the season’s last game, Relish was shown on Diamond Vision dreaming that he’d finally won, only to awaken and realize he’d slept through the final race.)

It was quite a cacophony, a veritable circus with baseball in the center ring. One time I overheard two out-of-town fans complaining about the endless noise and hoopla, lamenting that games were so much quieter back home in Mahoning Valley. I had to interrupt to note they were in Brooklyn now, one of the loudest places on Earth. “You can tell you’re no longer in Ohio because there are no cows in the outfield!” I pointed out.

Beyond the thrill of seeing live baseball back in Brooklyn, I haven’t been to any ballpark in the country—major or minor league—with such a unique and exhilarating ambiance. It starts right at the entrance, featuring a statue of a key moment in the history of Brooklyn and the nation, showing Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s shameful color barrier in 1947, standing with Dodger Captain Pee Wee Reese. The statue captures the iconic moment when Pee Wee, raised by a racist family in Kentucky, puts his arm around his tormented teammate on the field in Cincinnati, where Jackie faced vicious death threats. Each season I’ve posed in front of that statue with my godson, Jared, who over the years shot up until he was a good deal taller than me.

Once inside, the park is filled with enticing aromas—the most potent being Nathan’s hot dogs, sold at concession stands and tasting just as good as at the famous eatery’s original outlet a few blocks away. If the action on the field or in the stands isn’t exciting enough, there’s the weekly Coney Island fireworks that go off every Friday night promptly at 9:45 p.m., regardless of whether the Cyclones are home—creating a surreal atmosphere if they are still playing beneath the explosive display.

Fans cheering for the home team can clearly hear the cries of thrill seekers on the nearby Cyclone, the country’s nearly 100-year-old wooden roller coaster, for which the team is named. (I only summoned the nerve to take the ride once, when I was a fearless teen, but never went on again after experiencing the initial 85-foot drop at a 60-degree angle at about 60 miles per hour.) A much less frightening ride, the B&B Carousel, built in 1906 but recently restored to its original grandeur, operates right behind the park, just off the boardwalk. Many other attractions, from bungee jumps to bumper cars, are a few blocks away, as is the New York Aquarium.

For those seeking some fresh sea air, stroll past the carousel and across the boardwalk to Steeplechase Pier, extending 1,040 feet into the Coney Island surf, filled with those hoisting fishing poles and crab traps, along with half-naked sun bathers, leather-skinned old timers, and hordes of kids exuding enough energy to light the ballpark.

To top it off, down the first-base line, just beyond the rightfield fence and the Cyclones’ bullpen looms the last remnant of Steeplechase Park’s glory days—the 262-foot-tall Parachute Jump. First opened during the 1939 World’s Fair in Queen’s Flushing Meadow (where the Cyclones’ parent New York Mets now play), it tantalized and terrified riders for 23 years after moving to its current location in 1941. According to the New York City Parks Department, the six-sided steel tower held a dozen drop points, accessible by six-foot steel arms. Each parachute had a seat for two hanging beneath it. Riders were lifted by a cable to the top of the tower, then dropped before “floating” gently to the ground (though still supported by a steel cable, thank goodness). Climbing to the top took roughly a minute, while the stomach-churning descent lasted between 10 and 15 seconds. The seats resembled an open ski lift, leaving passengers’ legs dangling in the air. (My mother told me her shoes flew off, never to be recovered, during the one time she summoned the nerve to take the ride.)

While many sought to demolish the Parachute Jump after it closed for good in 1964, wiser heads prevailed. The surviving superstructure was certified as a landmark after its structural integrity was confirmed by engineers. Eventually the Jump was renovated and painted, and more recently was retrofitted to enable a series of spectacular light shows, a highlight of any Cyclones night game.

Nothing could stop the Cyclones from their quest to entertain the fans—not even Hurricane Sandy, which destroyed the park’s beautiful grass playing surface and forced the team to install artificial turf in 2013. I complained about the change in a message to the Cyclones, citing baseball superstar Dick Allen, who years earlier declared that “if a horse can’t eat it, I don’t want to play on it.” The team replied: “Sam, if a horse ate the toxic mess left behind by Sandy (the hurricane, not our glorious mascot), the poor beast would be dead.”

Cyclones deliver the moments that matter

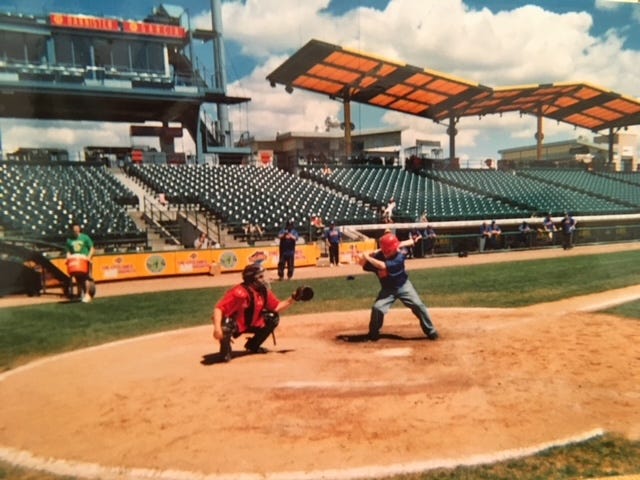

I’ve experienced so many memorable events in my quarter century following the Brooklyn Cyclones. One of the biggest was my own field of dreams moment, when for my 50th birthday a friend registered me for the Cyclones Fantasy Camp, where I took the field and worked out with some of the players. Former major leaguer turned broadcaster Harold Reynolds came by with a film crew to do a spot on us for ESPN, then stuck around to take part in the festivities. I caught one of his fly balls while playing centerfield and tried to hit against him—but to no avail.

Another highlight was standing next to former New York Met pitcher and 1986 World Champion Sid Fernandez on “Hawaiian Night,” when fans showing up in a Hawaiian shirt were allowed on the field during the national anthem. During “Greet the Fans” days, I kidded Michael Conforto about his holdout before signing with the Mets and told L.J. Mazzilli I’d gone to high school with his dad, to which he replied, “You must be really old!” I caught the only foul ball of my life while wandering over behind the Cyclones dugout to see one of my favorite players of all time, Gary Carter, in a Brooklyn uniform as a roving coach for the Mets’ minor league catchers.

But the best memory was in 2019, when I finally saw the Cyclones win a championship outright. Only one player (Brett Baty) from that squad has made it to the majors, while the star that season, shortstop Wilmer Reyes (perhaps the spiritual love child of Met shortstops Jose Reyes and Wilmer Flores), hit .323 and dazzled in the field and on the bases but never even made it to AA. Yet that team played hard, aggressive, and smart baseball, reflecting its manager, former Mets star Edgardo Alfonzo (who inexplicably was let go after the season despite his success in Brooklyn).

The 2019 Cyclones put together a big run at season’s end, winning the division on the last day and posting the league’s best record! Making the playoffs for the first time in seven years, they beat the Hudson Valley Renegades in the first round and then prevailed over the Lowell Spinners in the deciding game, in dramatic fashion.

Brooklyn jumped to a 2-0 lead but gave it right back. They fell behind 3-2 on a homer in the top of the seventh, but resilient as always that season, they rallied with a single by centerfielder Jake Mangum (now with Tampa Bay’s AAA farm team, the Durham Bulls, of movie fame), followed by an RBI triple down the right field line by rightfielder Antoine Duplantis and a go-ahead RBI single by third baseman Yoel Romero (who also saved a few runs with sparkling grabs and throws at third). The ninth inning was dicey, as the Spinners put the potential tying run on second and winning run on first with just one out. But lefty Andrew Edwards bore down and struck out the last two batters to WIN THE CHAMPIONSHIP!!!

Sharing that thrilling night with my wife and fellow Cyclone fan Cheryl was something I’ll never forget.

The Cyclones never had a chance to defend their title, first because the COVID pandemic forced the 2020 season to be cancelled, and then because the NY/Penn League was folded after 81 years during baseball’s traumatic minor league contraction. Luckily, the Cyclones survived! What a tragedy it would have been for Brooklyn to lose its baseball team a second time! They even moved up two levels to High A, just two leagues below the majors. The Cyclones used to start in mid-June, after the amateur draft, but although the team now plays a full 140-game schedule, I’ve yet to brave a night game in freezing April temperatures off Coney Island beach.

I look forward to seeing the latest Cyclones stars become key players for the Mets before long, including infielder Ronny Mauricio (out with a knee injury after an impressive cup of coffee with the Mets last September), Jett Williams (a speedster with surprising power who can play just about anywhere except catcher and first base), starter Blade Tidwell (what a great baseball name!), slick outfielder Nick Morabito (hitting .366 as of this writing), and two-way sensation Nolan McLean (who, looking to follow in the footsteps of the Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani, led Brooklyn in homers as a designated hitter and in strikeouts as a starting pitcher before being promoted to Binghamton last month).

Long live the Brooklyn Cyclones!!! May they keep me forever young!

Sammy’s Picks For The Greatest Cyclones Of All Time:

Starting Pitchers: Scott Kazmir (all-star game winner and AL champion with Tampa Bay; Olympic Silver Medalist), Collin McHugh (19-7 for Houston in 2015), Seth Lugo (current K.C. Royals ace), Dillon Gee (pitched eight seasons in the majors before finishing his career in Japan), Brian Bannister (finishing third in 2007 Rookie of the Year voting; becoming a pitching guru for three major league clubs and “widely regarded as one of the more innovative pitching minds in the game”), and the oft-injured but often outstanding Tylor Megill (still with the Mets)

Relief Pitchers: Joe Smith (side-armer who pitched in 866 games over 15 seasons for nine teams), Hansel Robles (411 games over eight years for five teams), Yusmeiro Petit (515 games in 14 years for six teams), and Paul Sewald (terrible with the Mets, going 0-13 combined in 2017 and 2018, but who became an outstanding reliever in Seattle and closed for NL champion Arizona in 2023)

Catcher: Francisco Alvarez

--Backups: Tomas Nido (still with the Mets), Drew Butera (who caught the last strike in the 2015 World Series for the K.C. Royals, against the Mets!), and Brett Kay (hit .311 for the 2001 co-champions)

First Base: Pete Alonso (all-time MLB rookie homer record with 53 in 2019)

--Backups: Lucas Duda (30 homers and 92 RBIs for 2014 Mets; 27 dingers with 73 RBIs for the NL Champion Mets in 2015), and “I Like” Ike Davis (32 homers with 90 RBIs for the 2012 Mets; played for Team Israel in the 2017 World Baseball Classic)

Second Base: Daniel Murphy (MVP of the NLCS for the Mets in 2015; hit .347 with 104 RBIs for the Nationals the following season)

--Backup: L.J. Mazzilli

Third Base: Wilmer Flores (who I saw make his debut at shortstop with the Cyclones at age 17!)

--Backup: Brett Baty (2019 Cyclone champion and still with Mets) and Joe Jiannetti (hit .348 for the 2001 co-champions)

Shortstop: --Amed Rosario (traded by the Mets to Cleveland for Francisco Lindor; .273 lifetime average in 881 games, now with Tampa Bay)

--Backup: Wilmer Reyes and Phillip Evans

Outfielders: Angel Pagan (two-time World Champion with San Francisco Giants), Michael Conforto (All Star who joined Mets midway through 2015 NL championship season; hit a pair of homers and batted .333 in 2015 World Series; hit .322 in the pandemic-shortened 2020 season), and Brandon Nimmo (outstanding leadoff hitter still with the Mets)

--Backups: Juan Lagares (Gold Glove winner), “Captain” Kirk Nieuwenhuis (who had the best bobblehead the Cyclones ever gave out, featuring Kirk in a Star Trek uniform), Frankie Coor, “Sonny” Concepcion, and Cory Vaughn (hit .307 with 14 homers and 56 RBIs in 72 games for the 2010 squad)

Pictured below (top to bottom): “Sammy Cyclones” at a recent game; getting ready to hit during my 2008 Cyclones Fantasy Camp game; with Godson Jared for our annual picture at the statue of Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese; beneath the iconic Parachute Jump; at bat against former major leaguer Harold Reynolds of ESPN; an aerial view of my field of dreams and fountain of youth.

Love your enthusiasm, my friend.

I’m in Brooklyn so I get this. My favorite Cyclone laughs are when foul balls to the right side into the parking lot were accentuated by the sound of a windshield breaking. Great advertising gimmick for an auto glass biz.