What Would the Founding Fathers Think?

While we may already be in a Constitutional crisis, not only isn't it the first, but we've faced far worse challenges only to see our freedoms expanded.

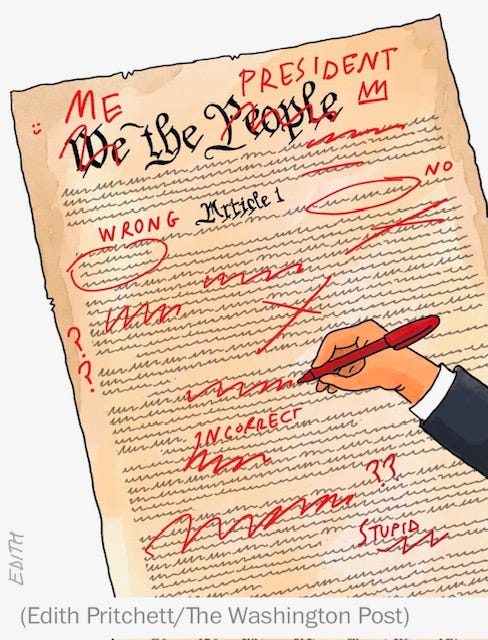

Approaching Independence Day in the midst of what many believe to be a constitutional crisis, I couldn’t help but wonder what the Founding Fathers would make of our failing separation of powers, collapsing system of checks and balances, and disintegrating rule of law. To my chagrin, it appears most would likely shrug and say, ‘I told you so,’ surprised only by how long the problematic Constitution they crafted had endured.

That’s not to say the Constitution is a goner as President Trump keeps exercising extraordinary powers, overriding congressional prerogatives, and ignoring court orders. The Constitution has already survived far more serious existential challenges, from the Civil War to Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, racial segregation in the south to the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II, as well as Sen. McCarthy’s witch hunts to President Richard Nixon’s Watergate coverup.

Yet it’s alarming to see Democrats and Republicans unable to agree these days on any point except that our country is becoming increasingly and dangerously divided. Our body politic resembles a feuding conjoined twin, two heads sharing one body and vital organs, but with separate brains diametrically at odds over policy.

It doesn’t help that we live in parallel media universes, locking ourselves in information bubbles designed to validate and fortify our existing preconceptions and beliefs. Rather than debate the opposition in good faith and seek compromises acceptable to all, we gripe about the other side among ourselves, dismissing inconvenient truths while demonizing the opposing party as evil enemies propagating “fake news” backed by “alternative facts.”

With our society so hopelessly fractured, can the Constitution still bind Americans together as one nation, or are we doomed to tear ourselves apart in a second civil war?

After studying our Founding Fathers for decades in history books and biographies, I realize we have serious daddy issues. Many Founders were deeply flawed, some shamefully perpetuating slavery, most determined to deny women the right to vote, and all okay with subjugating the indigenous population. Empty words were parroted about everyone here being created equal, “endowed with certain unalienable rights” too often routinely denied to this day.

But this does not negate the Founders’ extraordinary vision, courage, and political genius. They were the most capable, daring, and inspiring leaders our new nation could have hoped for in their time. They defeated the greatest power on Earth with a ragtag army and launched a practical democratic republic from scratch in a world long dominated by monarchs.

And despite multiple threats over the course of history, the Constitution they concocted—improved over time with liberty-expanding amendments—remarkably remains in effect in what has become the world’s richest and most powerful country. It’s hard to find too much fault with the Constitution’s shortcomings in the face of such success and staying power.

Yet I was surprised to learn that when the Constitution was first drafted, most of the major Founders were far from certain the guardrails they erected to diversify power and prevent autocracy would last for their own lifetimes, let alone 238 years. They voiced serious doubts even before the ink on the Constitution’s original parchment had dried. Their premonitions of doom, which resonate to this day, were well documented in “Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders,” by Dennis Rasmussen, a political scientist at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

Despite such deep and widespread pessimism, the Founders took their untested governing document off the drawing board and enthusiastically put it into practice, which was no easy task. Their perseverance should teach us that the Constitution isn’t worth the paper it’s written on unless we keep working to defend the protections against tyranny it promises to all, especially when elected officials abuse their authority and run roughshod over our liberties.

Why were many Founders so skeptical?

George Washington, hailed as the father of our country, warned in his Farewell Address that America was doomed to be torn asunder if party politics was allowed to prevail, perhaps even falling into despotism if one faction dominated all others in a tyrannical government.

“However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion,” he lamented.

Washington certainly got that right!

John Adams, Washington’s curmudgeonly vice president, doubled down on his president’s concerns. He doubted whether most citizens, particularly among the upper class, possessed enough civic virtue, moral fortitude, or patriotic fervor to put aside their own selfish interests and govern for the greatest benefit to all Americans. Adams also decried the country’s growing emphasis on commerce, wealth, and luxury among the elite, worried that widening inequality in income and education would inevitably result in a dominant commercial aristocracy controlling the government to further enrich themselves at the expense of the majority and the nation.

Adams certainly got that right!

Alexander Hamilton should be commended for putting the fledgling nation on a sound financial footing as the first Treasury Secretary (as well as for inspiring one of Broadway’s greatest and most innovative musicals). But while he wrote passionately to support the Constitution’s adoption in “The Federalist Papers,” he was extremely skeptical about giving the people too much power, fearing unchecked democracy would lead to the election of a tyrant. Hamilton had grave misgivings about the Constitution’s ability to “keep in check demagogues and knaves in the disguise of Patriots,” convinced that “mankind are forever destined to be the dupes of bold and cunning imposture.”

Hamilton certainly got that right!

Meanwhile, Mr. Jefferson—who kept slave labor throughout his life despite condemning slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence—was convinced differences between southern slave-holding states and northern free labor states papered over in the Constitution would prove to be irreconcilable. The result would be voluntary dissolution of the union, a civil war, or both, he warned.

While Jefferson unfortunately got that right, the Constitution ultimately survived the Civil War, albeit with major changes—including amendments abolishing slavery, establishing equal protection under the law, and guaranteeing men of all races the right to vote. (Although it would be another 50 years before the 19th Amendment finally gave women the vote as well.)

However, while Washington, Adams, Hamilton, and Jefferson were prescient in their own ways about why our republic might ultimately fail, it was James Madison, hailed as the “Father of the Constitution,” who never lost faith in our governing document’s resilience. Madison’s reasons for optimism should give us all hope for better days ahead in these politically turbulent times.

James Madison was an eternal optimist

Despite being a son of the south, a slaveholder, and protégé of Jefferson, Madison was anything but close-minded when it came to political compromise, joining archrival Hamilton in campaigning for the Constitution’s adoption while actively working to improve its protections against tyranny. In 1791, he filled glaring gaps in the Constitution by authoring its first 10 amendments, securing fundamental liberties concerning freedom of speech, assembly, the press, and religion.

Madison, who became our fourth president, believed firmly in the Constitution’s durability even before adding the Bill of Rights, dismissing the doubts of his fellow Founders and often hailing as strengths what his colleagues decried as fatal flaws. Nothing seemed to shake his confidence—not even when invading British forces set fire to his White House and the Capitol Building during the War of 1812.

Yet while Madison was an eternal optimist compared to his less sanguine compatriots, he was no Pollyanna, harboring his own misgivings. Besides bemoaning the lack of guaranteed civil rights in the original draft, Madison fought losing battles to include population-based representation in both the House and Senate as well as federal veto power over state laws. Later, he viewed with alarm the federal power of the purse established by Hamilton, the raising of a national standing army, and the wide discretion granted the President over foreign affairs.

But rather than disillusioning Madison, his concerns inspired him to work within the system and keep fighting in support of his own governing agenda. He started by working with Jefferson to form the Republican Party, rejecting Washington’s claim that parties prevented good governance. Madison believed parties were essential elements of a functioning democracy. He felt they consolidated disparate groups that agreed on central principles and policies, while creating the necessary organization and leverage to enact them into law.

Madison also rejected Hamilton’s concerns about spreading authority too thin to govern effectively. Believing that the more cooks there were in the governing kitchen the better chance there would be to avoid tyranny, he therefore ended up supporting power sharing with the states. Rejecting Jefferson’s aversion to financiers, he rechartered a national bank to promote commerce and economic growth. And despite disagreeing with many of its decisions, he grudgingly conceded final say over the Constitution’s practical application to the Supreme Court.

While conceding that this made for a messy and often frustrating way to govern, he wrote that, “A government like ours has so many safety valves, giving vent to overheated passions that it carries within itself a relief against the infirmities from which the best of human institutions cannot be exempt.”

Not even what Madison saw as President Andrew Jackson’s “capacious sense of executive power,” by acting without congressional authorization and defying Supreme Court orders, could undermine his faith in the Constitution as a bulwark against tyranny. To the contrary, he was confident that would-be autocrats like Jackson would be a passing problem.

Noting that Jackson’s “popularity is evidently and rapidly sinking under the unpopularity of his doctrines,” Madison predicted that such declining support during Jackson’s term meant “there is little reason to suppose that any succeeding President will attempt a like career.”

Let’s hope Madison is right about that!

In the end, Madison felt that come what may, the Constitution and the union it bound together would endure.

“I am far from desponding about the great political experiment in the hands of the American people,” he wrote. “Much has already been gained in its favor, by the continuing prosperity accompanying it through a period of so many years.” Madison believed that the abundance of liberties granted to citizens, enabling so much freedom and wealth, would trump the Constitution’s weaknesses while discouraging if not the rise, then at least the persistence of aspiring dictators.

Conceding that autocratic movements would inevitably emerge now and then, he insisted that “a sickly countenance occasionally is not inconsistent with the self-healing capacity of a Constitution such as I hope ours is, and still less with the medical resources in the hands of people such as I hope ours will prove to be.”

Where does America go from here?

As the Constitutional Convention was ending on September 17, 1787, Benjamin Franklin admitted the game plan for their new nation was far from perfect. However, he urged anyone still opposed to show humility, pleading with naysayers to “on this occasion doubt a little of their own infallibility.”

Franklin was certainly right about that!

Yet Franklin also had his doubts. When he emerged from the Constitutional Convention, Elizabeth Willing Powel, a prominent socialite and close friend of the Washingtons, asked whether the delegates had established a monarchy or a republic to rule what would become the United States of America. “A republic,” Franklin replied, explaining that he meant a state where ultimate power is held by the people and their elected representatives.

However, he famously added a foreboding caveat, warning that America would only remain a republic, “If you can keep it.”

Whether we can keep our democratic republic intact is ultimately up to us, not a 238-year-old document. As noted in the first three words of the Constitution’s preamble, “We the People” must call the shots. We need to keep reminding our political leaders about their responsibilities and the limitations of their power. We must vigorously hold them accountable while exercising our Constitutional rights to influence their actions, whether via petitions, public demonstrations, funding of like-minded parties, candidates, and advocacy groups, court challenges, investigative journalism based on undeniable facts, and most importantly through our votes.

As Dennis Rasmussen concluded in his book: “The Founders’ penchant for meeting deep disappointment with steadfast resolve is one that we would do well to emulate in the face of our own political tribulations.”

Is this the first time congresspeople were threatened by violence if they didn’t vote as ordered? The Minnesota killings must be in everyone’s mind.

Don't feel qualified to comment. My gut believes we are fine.